I’m on the road this week but luckily for us, my friend Elisa Bird agreed that I could share one of her great articles with you all. Given the frantic pace of aviation news lately, I thought perhaps a visit to an accident of yesteryear with Elisa’s insight would be welcome, specifically around the emergency…

I’m on the road this week but luckily for us, my friend Elisa Bird agreed that I could share one of her great articles with you all. Given the frantic pace of aviation news lately, I thought perhaps a visit to an accident of yesteryear with Elisa’s insight would be welcome, specifically around the emergency landing of Captain Carlos Dárdano in Louisiana in 1988. Thank you for the post Elisa!

Elisa Bird is a freelance journalist & researcher. She lives in the Canary Islands and loves pigs, aeroplanes, volcanoes, logic and justice.

When I wrote Gliding to Safety, in 2022, several people asked why I hadn’t included the famous “Miracle on the Hudson.” The answer is that it’s a wonderful story but very well-known, and although I’m as impressed by Captain Sullenberger’s remarkable airmanship as anyone, I’ve nothing new to add.

It feels more worthwhile to write stories where a new perspective gives better understanding, or those that deserve to be more widely known than they are. Like this one.

In some ways, it’s a similar story to the Hudson; loss of both engines. (For Sully, this was due to bird strike and his plane was an Airbus A320; for Carlos, it was hailstones and his plane was a Boeing 737–300.)

Neither plane had any chance of reaching an airport, but both had brilliant pilots who landed safely in a surprising place (Sully in a river, and Carlos on a muddy levée) and everyone survived.

Maybe the biggest difference is that this event happened 21 years before the Hudson, when there was limited social media and not the instant worldwide publicity we have now, so less people knew about it.

Captain Carlos Dárdano

In 1988, he was only 29, but with 13,410 flight hours, nearly 11,000 of them in command. His father was a pilot who worked in agriculture (crop-spraying, transporting workers and equipment).

As a child, Carlos loved to go with him and his father sat him on his lap and taught him to fly. He never wanted to be anything but a pilot, even flying on his days off.

He got his private pilot’s license at 16 while still at high school, and helped his father at work. It took him only five months to get his commercial license, and he was soon instructing others.

He gained experience at handling adversity too. One day in 1977, when he had only 100 hours of flying solo, his landing gear broke. He calls this the only time he was scared, but he reached an airport safely.

ECHO El Salvador map, by JRC, EC, 27 November 2014. wikimedia commons This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

In the 1980s, he was flying a Piper Arrow air taxi, transporting a couple and their child to a meeting. When they arrived, nobody was there and the place was eerily quiet.

This was during the civil war in El Salvador, and someone started shooting, hitting Carlos in the face and hitting the plane several times. Despite this serious injury, he got the passengers back in the plane and took off, flying low to avoid being seen. They reached Ilopango airport, which had an ambulance ready.

Going too fast, the ambulance nearly crashed on the way to hospital. When he woke after a six-hour operation, Carlos knew the bullet had destroyed his left eye. His biggest concern was that he might lose his American pilot’s license. TACA’s American operations were based in New Orleans.

The rules are different now, but he was lucky. After three months of flying accompanied by doctors and inspectors, who all agreed that he was flying perfectly, he was certified airworthy with a medical waiver, and returned to work as First Officer on a BAC-111.

When he went to Aerolineas Argentinas to upgrade to Captain, they had doubts about him because they had no experience of one-eyed pilots, but accepted the waiver on his US license.

TACA flight 110, 24 May 1988

TACA (Transportes Aereos Centro Americanos) was El Salvador’s national airline. It had a complicated history, starting in 1930s Tegucigalpa, Honduras, as a cargo airline. In 1940, they added a passenger service, based in San Salvador.

The plane, Registration N75356, was a Boeing 737–300, with CFM-56 turbofan engines. Almost new, it first flew on 26 January 1988. TACA had bought it only two weeks before this incident.

On board were seven crew and 38 passengers. The First Officer, Dionisio López, was nearly as experienced as Carlos with 12,000 flight hours. The two had often flown together and were friends. An Instructor Pilot, Arturo Soley, was also on the flight deck, to monitor the performance of this new plane for the airline.

Leaving on 23 May, they were to fly from San Salvador to New Orleans, with a stopover in Belize. They had to stay the night in Belize because the battery had gone flat while awaiting delivery and the engines wouldn’t start. Maintenance installed a new battery and they left next day.

Everything was normal until they were approaching New Orleans at FL350 (35,000 feet). They were having fun, showing passengers their new, modern, flight deck, which was allowed then.

Their radar weather map showed heavy rain storms, and the crew selected a route round the worst areas, marked in red on the map. But the map showed only the nearest weather, and they encountered heavy rain, hail and turbulence.

Before entering clouds at FL300, the Captain selected continuous engine ignition and activated anti-icing systems. Seeing the size of the storm they were entering, he was worried about damaging the plane. He was right.

This is a photo of the damage to the nose of the plane:

And this is some of the damage to one of the engines:

The industry hadn’t trained pilots for the loss of both engines, because manufacturers then didn’t believe it could happen.

At FL165, as they continued descending, both engines flamed out. The electrics and instruments failed. The loss of thrust and electrical power meant they were now gliding. They tried unsuccessfully to re-start the engines, which lit up but could not accelerate to idle.

A standby horizon allowed them to level the plane, but the clouds were too thick for the crew to see outside. Then they got the Auxiliary Power Unit (APU) to run on its batteries, which luckily were new. This restored the necessary electrics and hydraulics for landing.

Now they could communicate again. Air Traffic Controllers at New Orleans who saw them disappear from radar thought they had crashed, and were greatly relieved when the APU started up and First Officer López contacted them with a mayday call.

ATC sent them vectors, but they couldn’t reach the airport. ATC then offered them a possible landing at New Orleans Lakelands, but they were losing too much speed and altitude to reach that airport either.

Their only obvious option was a water landing in a Louisiana swamp. Captain Dárdano lined up with a canal East of New Orleans city, gliding as far as was possible without stalling.

First Officer López went through the ditching checklist to configure the plane; at about 1,000 feet he noticed the levée, near the Intercoastal Waterway and Mississippi river gulf outlet. He pointed this out to the Captain, who agreed it would be the best place to land.

To straighten the plane and slow it down, the Captain did a manouevre called a “side-slip.” This is commonly used with small, private planes, but it worked with the Boeing:

They landed perfectly on the grass strip, 6,060 feet (1818 meters) long and 120 feet (36 meters) wide, like this:

The passengers, keen to get out, were evacuated, but then it started raining so the pilots stayed in the plane until it stopped.

The causes of the incident were:

- TACA flight 110 had inadvertently flown into a Level 4 thunderstorm.

- Although the CFM-56 powerplants were certified to meet FAA standards, the engines had flamed out due to water ingestion from heavy rain and hail.

- Referring to “inadequate design of the engines,” they noted that the FAA standards did not account for the amount of water this flight encountered.

- The engine design has since been modified, and pilots now have a checklist for this rare type of event.

To conclude, let’s tie up the loose ends

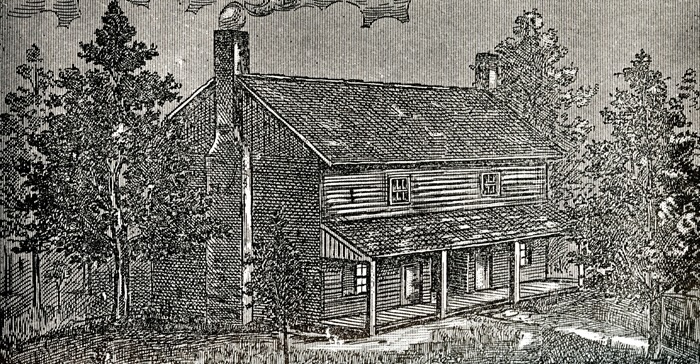

Boeing engineers and test pilots took N75356 from the levée to a nearby NASA facility, and installed new engines.

It took off from Saturn Boulevard, built on top of a World War II era runway, for Moisant Field. It was back in service for TACA until March 1989. It had several changes of ownership, and was retired in December 2016.

TACA airlines ceased operations in 2013, after merging with Avianca, and are now operating as Avianca El Salvador.

Captain Carlos Dárdano announced his retirement from commercial flying in September 2023, after 49 years’ service. Before that, he helped train his son, who flew as his First Officer. He still does aerobatics, and other aviation work.

He recommends pilots to learn aerobatics, because it helps them to understand and work with the plane. He also believes that even in these days of computerization, being able to fly manually is still useful.

It takes exceptional skill and some luck to get out of difficulties in such an imaginative way. But it also takes opportunity, which is even rarer. There must be other professional pilots capable of doing what Carlos and Sully both did, but they are probably very glad they never needed to.

Sources:

https://www.elsalvador.com/noticias/nacional/capitan-carlos-dardano-jubilado/1087314/2023/

Interview with Captain Carlos Dárdano, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kT4_4_jwj-A&list=WL&index=18

https://www.alternativeairlines.com/taca-airlines

https://aviation-safety.net/asndb/326548

https://simpleflying.com/34-years-ago-this-week-the-miracle-of-taca-flight-110/

One of the Most Amazing Aviation Stories EVER Told, Mentour Pilot, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H5UUr9RXfTY&list=WL&index=10

Thank you so much Elisa for sharing your article with us! Hopefully no one reading will end up having to land on a drowned engine grass strip, but it’s always reassuring to know that there’s someone else who has had it worse!

If you enjoyed Elisa’s article and want to read more, you can follow her on Medium, where she writes about history and disasters of all types.